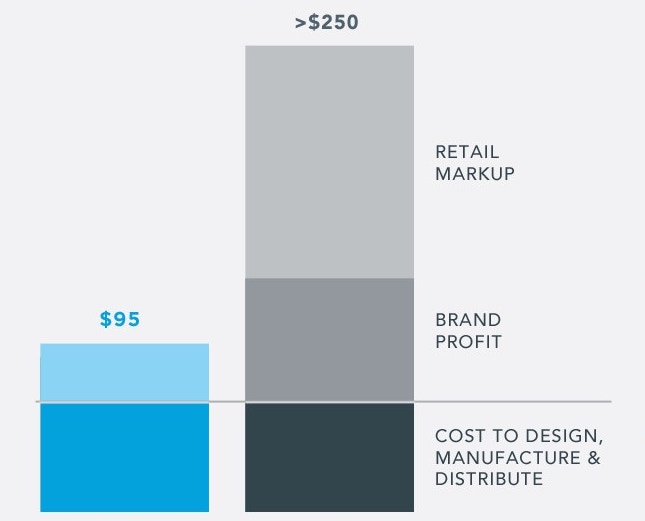

In the age of Direct-to-Consumer brands, retailers have become a popular enemy. Their entire industry has been reduced to just “middlemen” – some intermediate step that adds no value and instead adds cost. We’ve all seen the ubiquitous direct-to-consumer graph – how marketing, retailers, and everything else just adds layers of cost on top of an already completed product. But is it really that simple? Can an entire industry be simplified down to part of a chart?

While it’s correct that going through a retail store will technically make an item cost more than it would if you walked up to a factory and bought one right off the assembly line, the truth is more nuanced than that. And even if costs are indeed higher, a good retailer can bring benefits with them that often make up for the difference.

Before I get too far into this, I just want to define some things for clarity. These aren’t technical definitions, just how I will be referring to all the parts of this process in this article.

- Brand: a company that designs and/or manufacturers products and sells them primarily through retailers. Example: Common Projects

- Manufacturer: a company that produces products. They may sell them to brands or to retailers or direct-to-consumer. Example: Filson

- Retailer: a company that primarily buys products from brands (often to their own specifications) and then sells them to the end consumer. Example: Nordstrom

- Direct-to-Consumer brand (DTC): A company that designs products and sells them directly to the end consumer. Example: Warby Parker

- End Consumer: you!

So with all that said, here are some common advantages of going the traditional route rather than DTC:

- Better products. Because brands don’t have to spend as much time dealing directly with customers, they can focus more on creating their products. On top of this, a good retailer will know how to take a brand’s offerings and tailor them to the style of their store and their customers. Have you ever noticed how the Armoury’s collection of Carmina shoes looks so much better than the ones Carmina offers on their own site? It’s because the Armoury knows how to mould Carmina’s offerings into a more holistic and thoughtful collection for their store.

- Better customer experience. Likewise, because retailers don’t have to spend their days managing supply chains, sourcing materials, and prototyping new products, they can focus on giving the end customer the best experience possible. It’s no surprise that niche retailers are often lauded for their for exceptional customer service – unlike most DTC brands, they have the bandwidth (and margin) to do so.

- New brands and new products. One of the most important things that a good retailer does is help unearth new brands and products and introduce them to the market. Who had heard of Ring Jacket before the Armoury brought them to the scene? Same with Carlos Santos from Skoaktiebolaget, Formosa from No Man Walks Alone, and so on. These brands (and many others) are part of the menswear lexicon now, simply because retailers found them, took a risk, and introduced them to all of us. This continual expansion of available products, styles, and designs is critical to the success of the industry – nobody wants to see the same thing from every store every season.

- Trust and experience. Unlike the new surge of DTC brands, most retailers and brands are fairly well-established. Many have been around for decades, and have been honing their products and stores that whole time. This stands in stark contrast to young DTC brands who are often embarking on their business ventures with little to no experience.

- DTC brands have margin requirements, too. Because DTC brands have to manage the whole process (manufacturing, logistics, marketing, website, customer service, etc), they generally need more margin than a regular brand to make things sustainable. Plus, a large number of DTC brands experiment with selling their products to retailers at some point (and who can blame them?) so they have to save some margin for that. All of this is to say that the difference in margins is not always as stark as it’s often made out to be.

- Access. There are many products that we would simply not have access to if it weren’t for retailers. How else would you get your Japanese denim, Italian suits, and British footwear if it weren’t for retailers that helped bring them to you?

Retailers aside, there is another fallacy with the DTC value proposition – they always claim to be as good as the “gold standard” product, but without the markups. The problem is that this is never true. While it’s very possible that a DTC product offers a higher value, I’ve never seen one offer a better product. Is there anyone out there that would rather have a pair of Gustins over a pair of 3Sixteens? How about a pair of Warby Parkers over Oliver Peoples, or Linjer over Frank Clegg, or Greats over Common Projects? If price is removed from the equation, any smart customer would prefer the originator, because it is an objectively better product (not to mention the fact that most people would rather own “the original” and not an imitator). As mentioned above, this is due in large part to the fact that traditional brands have had more time to work on their products. Not only have they generally been around for much, much longer (decades as opposed to a couple of years), but they can spend more time honing their product as they aren’t as busy trying to manage every part of the process.

Of course, there are plenty of retailers that are out there increasing costs and adding little to no value. There was a time where proximity alone was enough of a value-add to make a retailer successful – if you were in a high-traffic area and had access to affluent customers, you could sell stuff. With the huge swing to e-commerce over the past 20 years, this is no longer as true as it once was. If you’re a store that only sells things like APC New Standards, Common Projects, and Filson bags straight out of the catalog, I can’t feel that bad for you if competition from DTC brands has caused sales to slump.

Retailers have an excellent opportunity to bring new products to the end customer and to do so with great service; if that opportunity is being wasted, then I can’t help but agree with the mood of the DTC brands. And there are plenty of stores out there like this – I mean, can you tell the difference between Nordstrom, Bloomingdales, Saks, and the rest? I sure can’t.

Now, all of this isn’t to say that there’s anything wrong with direct-to-consumer brands (as much as it may have sounded like it). I have many products from companies like these, and quite a few of them are making great stuff at a great price. And as someone with a relatively unimpressive income, I can’t always go to a retailer to buy their products, even if I want to. Plus, the quick product development timeline and relative ease to being things to market means that we have seen rapid innovation from many brands. Take companies like Stoffa, Suitsupply, Meermin, and so on – they’re offering more than just a cheaper way to get a product, they’re offering a whole new approach. Plus, the explosion of DTC brands has increased pressure on retailers because they’re all competing for the same customers – this competition has made the good retailers step up their game, and I think we all benefit from that.

At the end of the day, there are plenty of DTC brands making exceptional products and offering a great experience to customers, and there are some that are offering a lower price and nothing else. Likewise, there are retailers that are changing the very landscape of the menswear scene, and others that are skirting by on reputation alone. Ultimately, it comes down to the context of the product you’re looking at and the place you’re looking to buy from – I just recommend that you don’t cut out the middleman entirely.